The Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AMLA) is the most significant anti-money laundering legislation passed by Congress in several decades. The Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) is part of AMLA, which, in turn, is part of the National Defense Authorization Act enacted on January 1, 2021. The CTA provisions in the AMLA authorize the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) to collect beneficial ownership information and disclose it to appropriate recipients, including federal law enforcement.

The AMLA (including the CTA) provides for:

On January 1, 2024, the CTA introduced requirements around beneficial ownership transparency. It developed a new category of entities required to comply with the law as “reporting companies” and set out requirements for these companies to keep a record of their shareholders or ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs) and report this information and any subsequent updates to FinCEN. A beneficial owner is an individual who owns or controls (directly or indirectly) at least 25 percent of the ownership interest or exercises substantial control over an entity. Beneficial ownership information includes (BOI): full name, date of birth, current address, and a distinctive identification number. In November 2023, FinCEN issued a rule detailing how to use an entity FinCEN identifier to report BOI if three conditions are met:

An entity FinCEN identifier is a unique identifying number issued to reporting companies that have filed their initial BOI reports with FinCEN. The CTA applies to US entities and foreign entities doing business in the US. New reporting requirements came into effect on January 1, 2024, with companies that are already incorporated required to share BOI by January 1, 2025, and companies established after 1 January 2024 required to share BOI with FinCEN within 30 days. In September 2023, however, FinCEN proposed to extend the filing deadline for businesses created during the first year requirements apply (between January 1, 2024, and January 1, 2025) from 30 days to 90 to allow additional time to understand the requirements. After January 1, 2025, the filing deadline will remain 30 days from incorporation. Company directors who do not comply could pay up to $500 per day (up to $10,000) and face jail time of up to 2 years. Businesses will need to update FinCEN with any material changes. FinCEN published a notice of proposed rulemaking in December 2022 detailing who may have access to BOI contained in the FinCEN database. This includes domestic government agencies (including federal agencies working in national security, intelligence and law enforcement, Treasury officers, and state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies), authorized foreign requesters such as foreign law enforcement agencies, judges, prosecutors, central authorities, or competent authorities via federal intermediary agencies, and financial institutions and regulatory agencies to meet CDD compliance requirements. Financial institutions must have a company’s consent to access that information and have in place certain administrative, technical, and physical safeguards to protect the confidentiality of BOI, including security standards. FinCEN has issued Beneficial Ownership Information Reporting Guidance, including FAQs, key filing dates and questions, and a Small Entity Beneficial Ownership Information (BOI) guide to help companies comply with the CTA. FinCEN will publish additional guidance and educational materials here, including videos, infographics, and compliance guides. In the proposed rulemaking on access to BOI, it was noted that FinCEN continues “to face resource constraints in developing and deploying the Beneficial Ownership IT System.” However, the system went live on January 1, 2024.

The CTA required the Treasury to revise the customer due diligence (CDD) requirements for financial institutions within one year to eliminate unnecessary or duplicative requirements resulting from the new requirements for beneficial ownership by reporting companies.

The CDD rule requires covered financial institutions to identify and verify the identities of their customers. This includes identifying each natural person who directly or indirectly owns 25 percent or more of the equity interests of a legal entity customer and identifying at least one natural person who has “significant responsibility to control, manage or direct” a legal entity customer. It also includes maintaining risk-based procedures to verify the identities of those persons, which includes at least all of the elements currently required under the Customer Identification Rule.

The rule also requires covered financial institutions to obtain a certification from the individual opening an account on behalf of a legal entity that identifies individuals who meet the definitions under the ownership or control prongs.

It also expects such institutions to, on a risk basis, maintain and update customer information by establishing policies, procedures, and processes for determining whether and when, based on risk, to update customer information to ensure that customer information is current and accurate.

The definition of a “Reporting Company” includes all private, for-profit entities that are not otherwise required to register with the SEC, the CFTC, or a state insurance authority, employ fewer than 20 full-time employees, and report less than $5 million in revenue on their federal income tax returns. This definition includes corporations, limited liability companies, and other entities that meet the above specifications.

A reporting company must provide certain information to the FinCEN database for each “beneficial owner,” including the owner’s (i) full legal name, (ii) date of birth, (iii) current residential or business address, and (iv) the unique identifying number of an acceptable identification document (for example, a driver’s license or a passport).

The AMLA reflects the US government’s focus on punishing noncompliance with the BSA and other anti-money laundering rules. Accordingly, it sets out new provisions to punish anti-money laundering violations, with penalties of 10 years in prison and a $1 million fine for:

AMLA introduces penalties for persons who are convicted of BSA violations – applied in addition to the existing fines that may be imposed for the same crimes:

The AMLA expands U.S. law enforcement’s ability to subpoena bank records from foreign financial institutions that maintain a correspondent banking relationship in the United States. Previously, the US DOJ or Treasury could issue subpoenas to request records limited to correspondent accounts of a foreign bank maintained in the U.S.

Under AMLA, the authorization is expanded to include the power to subpoena records relating to any account at a foreign bank subject to an anti-money laundering investigation, a civil forfeiture action, or any federal criminal investigation. The revised statute also requires foreign banks to authenticate the requested records, making it easier for prosecutors to use them as court evidence. If the bank fails to comply with the subpoena requirements of the statute, the government may assess civil penalties of up to $50,000 per day and seek an order from a U.S. district court compelling the foreign bank to appear and produce records or be held in contempt of court. The consequences of these new provisions are potentially significant. The changes are designed to allow federal investigators to obtain foreign bank records through subpoena power rather than relying only on international treaties or cooperation agreements.

Although the law is primarily aimed at combatting money laundering, the broad scope of the statute’s language regarding subpoena power relating to “any investigation of a violation of a criminal law of the United States” means that it can and likely will be used by law enforcement in other matters involving criminal conduct, including high-profile white-collar crimes such as tax evasion, foreign corrupt practices, money laundering by foreign persons, as well as international drug trafficking and national security violations.

However, some potential limitations exist on the expanded subpoena power, including conflicting local bank secrecy and confidentiality statutes, interpretations related to jurisdiction, and judicial review of the burden posed by a specific subpoena. It will be up to the courts to determine the enforceability of a subpoena issued in accordance with AMLA.

1970 to 2021: The Anti Money Laundering Act Timeline: Our US AML Act timeline sets out the most significant moments of AML regulation in the United States, from the introduction of reporting and record-keeping requirements in 1970 to the response to terrorism threats and emerging fintech and cryptocurrency risks in the 21st century.

The AMLA contains provisions prohibiting politically exposed persons (PEPs) from falsifying the source of funds, ownership or control of assets, or concealing or misrepresenting such information to a financial institution. Any violations of the above prohibitions are subject to fines, imprisonment, or forfeiture. Entities that are of primary money-laundering concern face similar prohibitions.

Neither Bank Secrecy Act/Anti-Money Laundering (BSA/AML) regulations nor the AMLA defines a “Politically Exposed Person”. However, US government agencies have stated that they do not interpret the term to include U.S. public officials. The term “PEP” is customarily used in the financial industry to refer to foreign individuals who are or have been entrusted with a prominent public function, as well as their immediate family members and close associates. By virtue of their position or relationship, such individuals may pose a higher risk that their funds may be the proceeds of corruption or unlawful activities.

Although due diligence must be performed on accounts and transactions conducted by PEPs, not all such transactions and accounts are necessarily higher risk. The level of risk associated with PEPs varies in accordance with the country of legal residence, the prior history associated with the individual, and the type of activities conducted by the individual.

FinCEN provides guidance that PEPs should not be confused with the term “Senior Foreign Political Figure” (SFPF), which is defined under the BSA regulations. FinCEN guidance states that Senior Foreign Political Figures are a subset of PEPs.

BSA regulations define the term Senior Foreign Political Figure as “a current or former senior official in the executive, legislative, administrative, military or judicial branches of a foreign government (whether elected or not); a senior official of a major foreign political party; or a senior executive of a foreign government-owned commercial enterprise; a corporation, business, or other entity that has been formed by, or for the benefit of, any such individual; an immediate family member of any such individual; and a person who is widely and publicly known (or is actually known by the relevant covered financial institution) to be a close associate of such individual.”

In the United States, AML obligations with respect to PEPs include specific enhanced due diligence obligations for private banking accounts that are established, maintained, administered, or managed in the United States for senior foreign political figures, and general due diligence procedures required for all politically exposed persons. Applicable due diligence policies should be incorporated into the financial institution’s anti-money laundering program.

Formerly, the Department of the Treasury had the discretion to distribute awards to whistleblowers but not the obligation to award payments. Payments were capped at $150,000 and, as such, were said to have little impact on money laundering enforcement.

AMLA changes that by eliminating the government’s discretion to pay an award and mandating payments, increasing the potential amount of whistleblower awards, and providing additional protection specific to money laundering whistleblowers. The protections are modeled after the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act’s (DFA) provisions. Certain classes of individuals, such as regulatory and law enforcement officials and those who participated in the wrongdoing, are prohibited from receiving an award.

AMLA eliminates the $150,000 cap on BSA/AML whistleblower awards, replacing it with a payment ceiling of 30 percent of the government’s collection if the monetary sanctions imposed exceed $1 million. Factors to be considered by the government when deciding the amount of the award, including the significance of the information, the degree of assistance provided, and the programmatic interest of the Treasury in deterring violations, mirroring the factors provided in the DFA.

Certain limitations in the law may, however, have the effect of lessening the impact of the whistleblower awards. The monetary sanctions on which rewards will be calculated exclude payments for forfeiture of assets, restitution, and victim compensation. This may significantly limit the size of a whistleblower award because large forfeiture judgments are generally sought by the government when resolving BSA/AML matters.

Whistleblower protections prohibit employers from engaging in retaliatory acts, such as discharging, demoting, threatening, or harassing employees who provide information relating to money laundering or BSA violations to the Attorney General, Secretary of Treasury, regulators, and others. This provision was also modeled after the provisions contained in the DFA. In addition, internal whistleblowers who report suspected wrongdoing to their employer rather than the government are afforded protection under the Act.

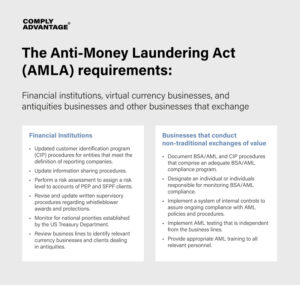

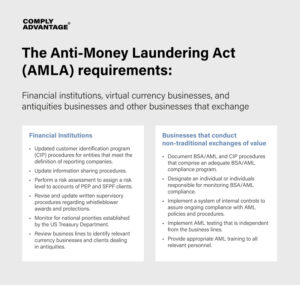

AMLA expands BSA to regulate businesses that conduct non-traditional exchanges of value, including virtual currencies and antiquities. AMLA provisions state that individuals and entities that exchange or transmit value using a product that substitutes for currency (for instance, cryptocurrency) are subject to BSA registration and compliance requirements. AMLA also amended the definition of a “financial institution” to include entities conducting antiquities businesses.

AMLA provides for Congressional oversight of deferred prosecution agreements and non-prosecution agreements relating to BSA. AMLA mandates the Department of Justice to submit annual reports to Congress containing details of the deferred prosecution agreements and non-prosecution agreements relating to BSA violations that were entered into, amended or terminated with any person during that year.

The AMLA requires the Treasury Department to establish national priorities to enhance anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing. The AMLA requires financial institutions to incorporate the identified priorities into their risk-based AML compliance programs. Issued on June 30, 2021, the first set of FinCEN national priorities are:

The AMLA allows financial institutions to share AML/BSA-related information with their foreign branches, subsidiaries, and affiliates. It codifies prior guidance authorizing these institutions to collaborate with other financial institutions to provide information regarding potential suspicious activity and help enhance AML/BSA compliance. Treasury and FinCEN are required to conduct a three-year pilot study regarding information sharing. The Treasury and other supervising agencies will establish “best practices” for these information-sharing arrangements.

Despite AMLA becoming law in 2020, it will continue to be implemented by the federal government in 2024. On July 3rd, 2024, FinCEN issued a proposed rule based on the authorization provided by the AMLA for the agency to “reevaluate the requirements of AML/CFT programs at financial institutions as part of the broader initiative to “strengthen, modernize, and improve” the U.S. AML/CFT regime.” The rule codifies long-standing best practices, such as the need for ongoing risk assessments and the requirement that all financial institutions designate a qualified AML/CFT officer. FinCEN also emphasizes that the proposed rule helps deliver on BSA requirements around access to banking services – put simply, if risk-based AML programs are more rigorously managed, FinCEN reasons this should ensure firms do not default to a “one-size-fits-all” approach that leaves “entire categories of customers” unable to access financial services.

FinCEN also hopes this proposed rule will help facilitate better feedback loops between itself, law enforcement, financial regulators, and financial institutions – another key goal of AMLA.

Finally, FinCEN – in line with AMLA – encourages firms to embrace technological innovation to help reduce challenges such as high numbers of false positive alerts in transaction monitoring systems.

Speak to one of our colleagues about how our financial crime risk management solutions can help meet your AML regulatory requirements and improve operational efficiency