The separation of powers has spawned a great deal of debate over the roles of the president and Congress in foreign affairs, as well as over the limits on their respective authorities, explains this Backgrounder.

The U.S. Constitution parcels out foreign relations powers to both the executive and legislative branches. It grants some powers, like command of the military, exclusively to the president and others, like the regulation of foreign commerce, to Congress, while still others it divides among the two or simply does not assign.

More From Our ExpertsThe separation of powers has spawned a great deal of debate over the roles of the president and Congress in foreign affairs, as well as over the limits on their respective authorities. “The Constitution, considered only for its affirmative grants of power capable of affecting the issue, is an invitation to struggle for the privilege of directing American foreign policy,” wrote constitutional scholar Edward S. Corwin in 1958.

Foreign policy experts say that presidents have accumulated power at the expense of Congress in recent years as part of a pattern in which, during times of war or national emergency, the executive branch tends to eclipse the legislature.

The periodic tug-of-war between the president and Congress over foreign policy is not a by-product of the Constitution, but rather, one of its core aims. The drafters distributed political power and imposed checks and balances to ward off monarchical tyranny embodied by Britain’s King George III. They also sought to remedy the failings of the Articles of Confederation, the national charter adopted in 1777, which many regarded as a form of legislative tyranny. “If there is a principle in our Constitution, indeed in any free Constitution, more sacred than any other, it is that which separates the legislative, executive, and judicial powers,” wrote James Madison, U.S. representative from Virginia, in the Federalist papers.

Daily News BriefMany scholars say there is much friction over foreign affairs because the Constitution is especially obscure in this area. There is not the intrinsic division of labor between the two political branches that there is with domestic affairs, they say. And because the judiciary, the third branch, has generally been reluctant to provide much clarity on these questions, constitutional scuffles over foreign policy are likely to endure.

More From Our ExpertsArticle I of the Constitution enumerates several of Congress’s foreign affairs powers, including those to “regulate commerce with foreign nations,” “declare war,” “raise and support armies,” “provide and maintain a navy,” and “make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces.” The Constitution also makes two of the president’s foreign affairs powers—making treaties and appointing diplomats—dependent on Senate approval.

Beyond these, Congress has general powers—to “lay and collect taxes,” to draw money from the Treasury, and to “make all laws which shall be necessary and proper”—that, collectively, allow legislators to influence nearly all manner of foreign policy issues. For example, the 114th Congress (2015–2017) passed laws on topics ranging from electronic surveillance to North Korea sanctions to border security to wildlife trafficking. In one noteworthy instance, lawmakers overrode President Barack Obama’s veto to enact a law allowing victims of international terrorist attacks to sue foreign governments.

Congress also plays an oversight role. The annual appropriations process allows congressional committees to review in detail the budgets and programs of the vast military and diplomatic bureaucracies. Lawmakers must sign off on more than a trillion dollars in federal spending every year, of which more than half is allocated to defense and international affairs. Lawmakers may also stipulate how that money is to be spent. For instance, Congress repeatedly barred the Obama administration from using funds to transfer detainees out of the military prison at Guantanamo Bay.

Congress has broad authority to conduct investigations into particular foreign policy or national security concerns. High-profile inquiries in recent years have centered on the 9/11 attacks, the Central Intelligence Agency’s detention and interrogation programs, and the 2012 attack on U.S. diplomatic facilities in Benghazi, Libya.

Furthermore, Congress has the power to create, eliminate, or restructure executive branch agencies, which it has often done after major conflicts or crises. In the wake of World War II, Congress passed the National Security Act of 1947, which established the CIA and National Security Council. Following the 9/11 attacks, Congress created the Department of Homeland Security.

The president’s authority in foreign affairs, as in all areas, is rooted in Article II of the Constitution. The charter grants the officeholder the powers to make treaties and appoint ambassadors with the advice and consent of the Senate (Treaties require approval of two-thirds of senators present. Appointments require consent of a simple majority.)

Presidents also rely on other clauses to support their foreign policy actions, particularly those that bestow “executive power” and the role of “commander in chief of the army and navy” on the office. From this language springs a wide array of associated or “implied” powers. For instance, from the explicit power to appoint and receive ambassadors flows the implicit authority to recognize foreign governments and conduct diplomacy with other countries generally. From the commander-in-chief clause flow powers to use military force and collect foreign intelligence.

Presidents also draw on statutory authorities. Congress has passed legislation giving the executive additional authority to act on specific foreign policy issues. For instance, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (1977) authorizes the president to impose economic sanctions on foreign entities.

Presidents also cite case law to support their claims of authority. In particular, two U.S. Supreme Court decisions—United States. v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corporation (1936) and Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company v. Sawyer (1952)—are touchstones.

In the first, the court held that President Franklin D. Roosevelt acted within his constitutional authority when he brought charges against the Curtiss-Wright Export Corporation for selling arms to Paraguay and Bolivia in violation of federal law. Executive branch attorneys often cite Justice George Sutherland’s expansive interpretation of the president’s foreign affairs powers in that case. The president is “the sole organ of the federal government in the field of international relations,” he wrote on behalf of the court. “He, not Congress, has the better opportunity of knowing conditions which prevail in foreign countries and especially is this true in time of war,” he wrote.

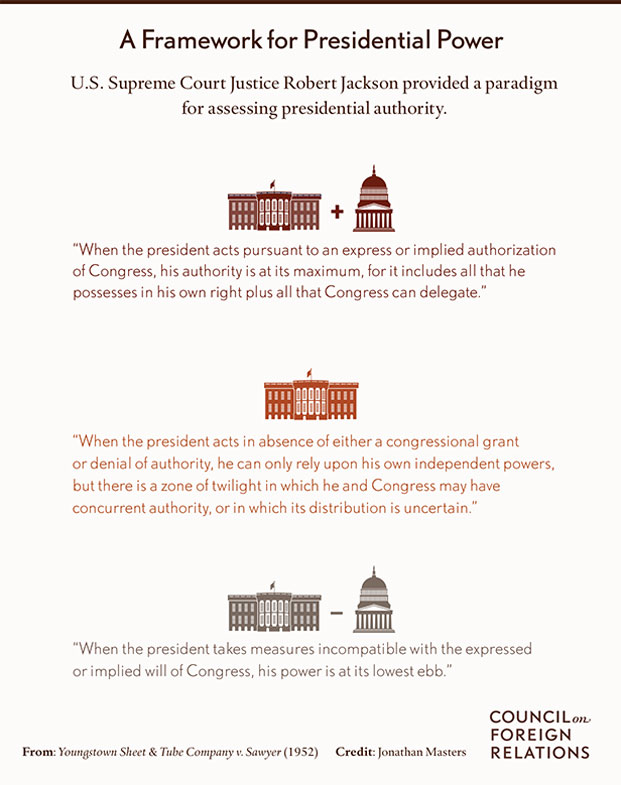

In the second case, the court held that President Harry Truman ran afoul of the Constitution when he ordered the seizure of U.S. steel mills during the Korean War. Youngstown is often described by legal scholars as a bookend to Curtiss-Wright since the latter recognizes broad executive authority, whereas the former describes limits on it. Youngstown is cited regularly for Justice Robert Jackson’s three-tiered framework for evaluating presidential power:

The political branches often cross swords over foreign policy, particularly when the president is of a different party than the leadership of at least one chamber of Congress. The following issues often spur conflict between them:

Military operations. War powers are divided between the two branches. Only Congress can declare war, but presidents have ordered U.S. forces into hostilities without congressional authorization. While there is general agreement that presidents can use military force to repel an attack, there is much debate over when they may initiate the use of military force on their own authority. Toward the end of the Vietnam War, Congress sought to regulate the use of military force by enacting the War Powers Resolution over President Richard Nixon’s veto. Executive branch attorneys have questioned parts of the resolution’s constitutionality ever since, and many presidents have flouted it. In 2001, Congress authorized President George W. Bush to use military force against those responsible for the 9/11 attacks; and, in 2002, it approved U.S. military action against Iraq. However, in recent years, legal experts from both parties have said the president should have obtained additional authorities to use military force in Libya, Iraq, and Syria.

Congress can also use its “power of the purse” to rein in the president’s military ambitions, but historians note that legislators do not typically take action until near the end of a conflict. Moreover, lawmakers are often loath to be seen by their constituents as holding back funding for U.S. forces fighting abroad. During the Vietnam War, lawmakers passed several amendments prohibiting the use of funds for combat operations in Vietnam and neighboring countries. Congress took similar measures in the 1980s with regard to Nicaragua, and in the 1990s with Somalia.

Foreign aid. Presidents have also balked at congressional attempts to withhold economic or security assistance from governments or entities with poor human rights records. For instance, during the Obama administration, senior U.S. military commanders said that, while well-intentioned, restrictions on U.S. aid complicated other foreign policy objectives, like counterterrorism or counternarcotics.

Intelligence. Congress began to claim a larger role in intelligence oversight in the 1970s, particularly after the Church Committee uncovered privacy abuses committed by the CIA, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and National Security Agency. Congress passed several laws regulating intelligence gathering and established committees to supervise the executive branch’s activities in areas including covert operations. Many presidents have protested these developments and claimed that Congress was encroaching on their prerogatives.

International agreements. The Senate has approved more than 1,600 treaties over the years, but it has also rejected or refused to consider many agreements. After World War I, senators famously rebuffed the Treaty of Versailles, which had been negotiated by President Woodrow Wilson. More recently, a small coalition in the upper chamber blocked ratification of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea despite the support of both Republican and Democratic administrations. Political hurdles associated with treaties have at times led presidents to forge major multinational accords without Senate consent. For instance, the Paris Agreement on climate change and the Iran nuclear agreement, both negotiated by President Obama, are not treaties. Thus, legal analysts say, future presidents could likely withdraw from them without congressional consent. The Constitution does not say whether presidents need Senate consent to end treaties.

Trade. The Constitution expressly grants Congress the power to regulate foreign commerce, but lawmakers have for decades provided presidents special authority to negotiate trade deals within established parameters. Renewal of this “fast track” trade promotion authority has become more controversial in recent years as trade deals have become more complex and the debates over them more partisan.

Immigration. Presidents are constitutionally bound to execute federal immigration laws, but there is considerable debate over how much latitude they have in doing so. Many Republican lawmakers said the Obama administration ignored the law when it established programs shielding undocumented immigrants from deportation. For its part, the administration said that it had broad discretion to decide how to spend the government’s scarce resources on enforcement. More recently, many Democratic lawmakers said President Donald J. Trump overstepped his constitutional and statutory authority when he attempted to block travelers from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States.

Federal courts, including the Supreme Court, weigh in from time to time on questions involving foreign affairs powers, but there are strict limits on when they may do so. For one, courts can only hear cases in which a plaintiff can both prove they were injured by the alleged actions of another and demonstrate the likelihood that the court can provide them relief. For instance, in 2013, the Supreme Court threw out a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of an electronic surveillance program, ruling that the lawyers, journalists, and others who brought the suit did not have standing because the injuries they allegedly suffered were speculative.

Another form of judicial restraint turns on the “political question” doctrine, in which courts decline to take sides on a major constitutional question if the judges say its resolution is best left to the president or Congress. For instance, in 1979, the Supreme Court debated whether to hear a case brought by members of Congress against the administration of President Jimmy Carter. The lawmakers claimed that the president could not terminate a defense pact with Taiwan without congressional approval. The court dismissed the case after a majority of justices found the underlying issue to be a political question, and thus outside the scope of their review.

However, the Supreme Court has weighed in on several cases related to the detention of terrorism suspects at the U.S. military prison in Guantanamo Bay. More recently, the court took on a dispute between the Obama administration and Congress over the recognition of Israeli sovereignty over Jerusalem. “It is for the president alone to make the specific decision of what foreign power he will recognize as legitimate,” the court held.

Presidents have accumulated foreign policy powers at the expense of Congress in recent years, particularly since the 9/11 attacks. The trend conforms to a historical pattern in which, during times of war or national emergency, the White House has tended to overshadow Capitol Hill.

Scholars note that presidents have many natural advantages over lawmakers with regard to leading on foreign policy. These include the unity of office, capacity for secrecy and speed, and superior information. “The verdict of history, in short, is that the substantive content of American foreign policy is a divided power, with the lion’s share falling usually, though by no means always, to the president,” wrote Corwin, the legal scholar.

Some political analysts say Congress has abdicated its foreign policy responsibilities in recent years, faulting lawmakers in both parties for effectively standing on the sidelines as the Obama administration intervened militarily in Libya in 2011 and in Syria starting in 2014. Lawmakers should emulate the activist measures Congress took to weigh in on foreign policy issues from the late 1960s to the early 1990s, they say. Policymakers can also significantly alter executive branch behavior simply by threatening to oppose a president on a given foreign policy issue.

In a series of blog posts, CFR’s James M. Lindsay examines the division of war powers between Congress and the president in the context of the U.S.-led military intervention in Libya.

President Trump’s foreign policy proposals may spur Congress into taking a more active role than it has in recent years, writes political science professor Stephen R. Weissman in Foreign Affairs.